Clickshare's Origins

In order to understand where we want to go, you need to understand the idea that prompted the creation of Clickshare in .

Origins | Four Party Model | Federated Identity | User Alliance | The Larger Vision

Origins

In 1994, we saw a train wreck coming for newspapers if they couldn't figure out how to make money referring their users to other peoples' content - across emerging "fat pipes" into the home. Otherwise, they were marginalized.

Today, that's becoming true. And the same fate is threatening cable companies and broadcasters.

- What's needed for consumers is a way for them to find, pay for - and be rewarded for - using and sharing content with one ID, one account, one-bill (or payment) simplicity across the public TCP/IP network.

- What's needed for content owners and marketers is a shared-user network for trust, identity and information commerce.

The network must allow multiple "user agents" to be rewarded for helping their customers find the information they need or want.

The network must allow multiple content providers to make money even when their content is broken into pieces and remixed by others.

And it must allow marketers to access a one-to-one relationship with their customers - always with the extend of that relationship understood and controlled by the consumer.

These four parties - the consumer, their user agent (we like the term "InfoValet"), the publisher/vendor and the network aggregation/tracking/settlement service - must all be able to share value across an open network.

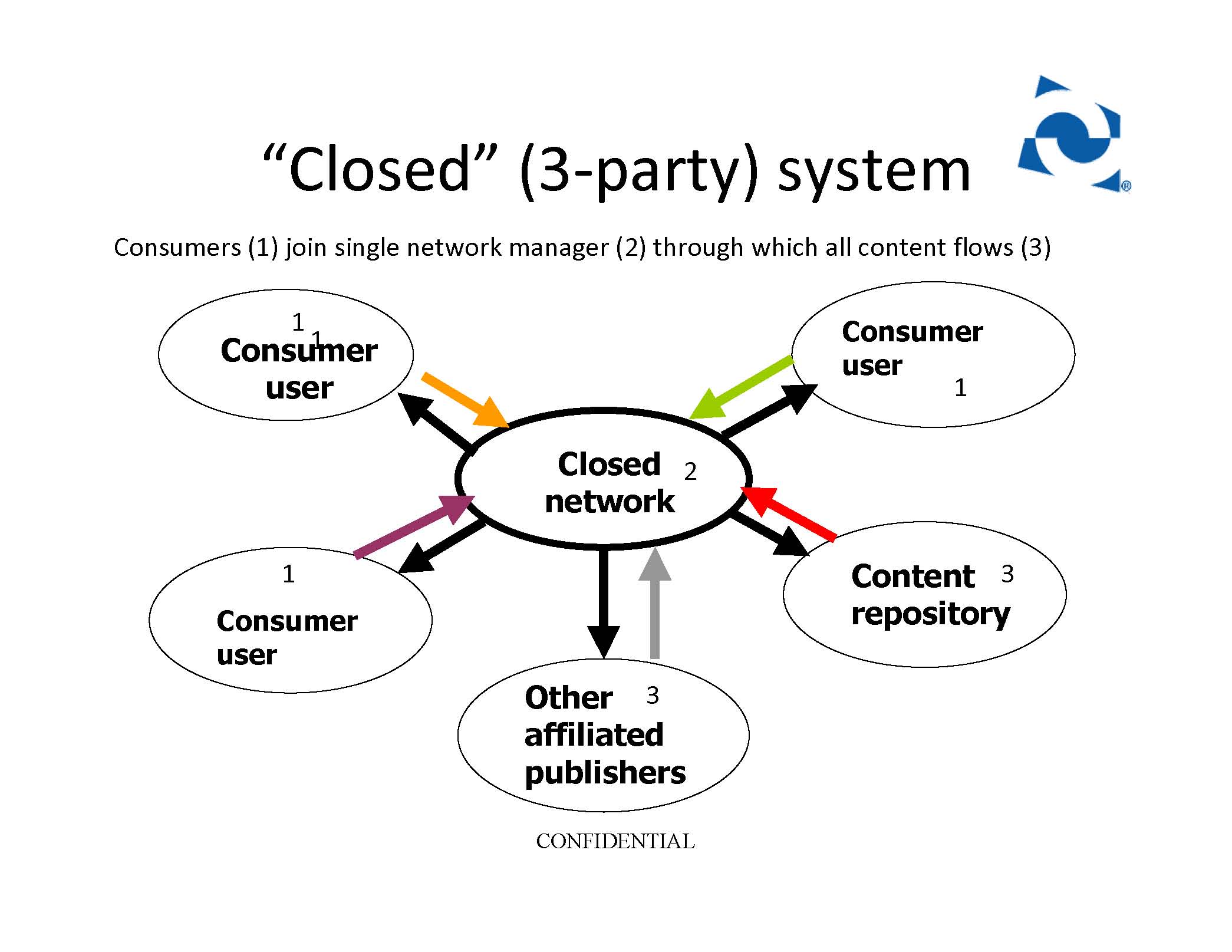

A three-party "closed" network - one big content provider for all or one big user agent for all - won't ultimately scale and will be inconvenient for users - like siloed ATM machines, iTunes, Facebook Credits or siloed tollway FastPasses.

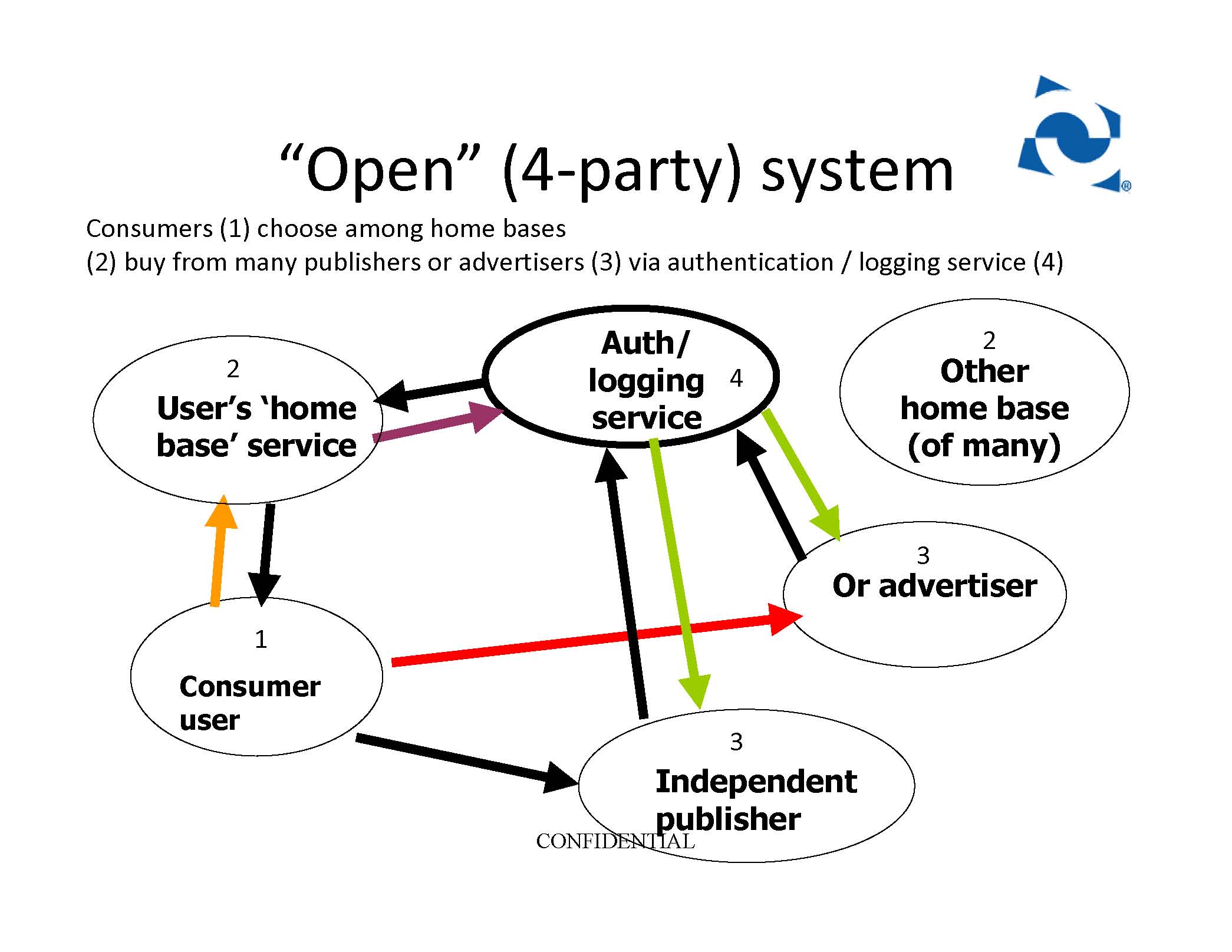

A four-party "open" network - unlimited user agents exchanging value with unlimited content providers/vendors on behalf of consumer users - like wireless phone call or bank interchange - will make the market for digital information - globally.

At Clickshare, we want to build that market.

The four-party model: Choice, control for consumers; opportunity for publishers?

The open Internet has shifted access and control of digital information largely from publishers to consumers. Many publishers are struggling to make money. Consumers have access to ubiquitous information, but have trouble sorting it or acquiring the most trustworthy knowledge.

How might we create a new playing field that affords increased choice and control for consumers, and new business opportunity for publishers as well?

Here's a scenario, which we'll call the "four-party model."

Several media organizations have built proprietary or closed systems to distribute and get compensated for their content, both editorial and advertising. Software programs abound to run and manage the systems. However successful the closed systems are, there lies outside their universe massive numbers of news consumers seeking and using additional news content.

Let me ask you to envision two initiatives – one involving available technology and the other requiring business collaboration - working together to expand the universe of users beyond the limits of these closed, proprietary systems, create an open marketplace for digital content, and enhance consumer privacy.

First, the open-marketplace technology would work with and expand the closed systems. It would allow news consumers to venture outside a publisher's proprietary system, subscribe to or pay for digital content from any other source. At the same time, news consumers from other proprietary systems can travel, visit, view and acquiring content from remote services. In either case, system capabilities allow tracking and payment to occur.

In short, the technology places in effect a hybrid closed/open system. Thus it provides unlimited audience and revenue growth potential for all participating information providers. Equally important, it makes it efficient for consumers to access news and information they choose – without boundaries and without multiple accounts or IDs.

Second, now please envision the business collaboration as an independent Information Trust Exchange Governing Association. It would foster and enforce open protocols to allow registered users in closed systems to be recognized, selectively and privately use their credentials to transact with any other participating closed system. The ITA would be a public-benefit organization with a global perspective and governance. It would not itself produce content or have consumers as customers. It would fostering technology that allows private networks to join, do business and compete. It would make and enforce marketplace rules respecting consumer privacy and choice.

A summit of major news, information and technology providers is necessary to embrace the ITA, invoke needed technology and open the digital-content marketplace.

A key insight driving this vision is the the idea of the open "four-party" vs. closed "three-party" approach to information commerce.

It was in November, 1994 that we first began thinking about "the four-party model." We formed a small team to help find a solution to what we saw as a looming train wreck for newspapers. When "fat pipes" - high-speed Internet services - reached American homes, people would be able to easily go anywhere for vital information. The role of the physical aggregator, the print newspaper, would be diminished.

And so we began thinking: How could we develop a service that would allow news organizations to take on a new role referring their users to digital information from anywhere - and getting paid for doing so. Then-colleagues David Oliver and Michael Callahan worked with the author on a solution - which came to be called Clickshare. The core idea was that news organization (or internet service providers, we thought), would become agents for consumers - similar to a real-estate broker who represents the buyer instead of the seller.

In days before the World Wide Web, information aggregators like Compuserve, AOL, Lexis-Nexis and others gathered information into their network and then sold it. Each was its own "silo" - you couldn't move from one to the other without changing networks and logging on with a different ID. That's the way Apple's iTunes store works today. They look like this:

In 1994, in the web information ecosystem, we expected there would be four parties - (1) the consumer end-user, (2) the vendor information provider (3) a neutral third-party who manages trust and transactions among all parties and (4) the consumer end-user's agent. In this way, a user could have one account with a single most-trusted "Information Valet," and that account would work at lots of other places - sort of like a credit card being presentable at stores worldwide. A good analogy is to Visa vs. American Express. Visa has no consumer accounts - it's bank members do. Banks re the fourth party. All American Express cards have accounts at Amex - the third party. Like Apple and iTunes.

The big distinction is that a four-party model is a fully distributed network approach, while the Amex, Apple etc. three-party approach is not. Content distribution and sales in a networked environment like the web should use an open, networked model in which any publisher can sell any content. In 1994, we thought a "four-party model" sustaining a trust ecosystem for information commerce would look like this:

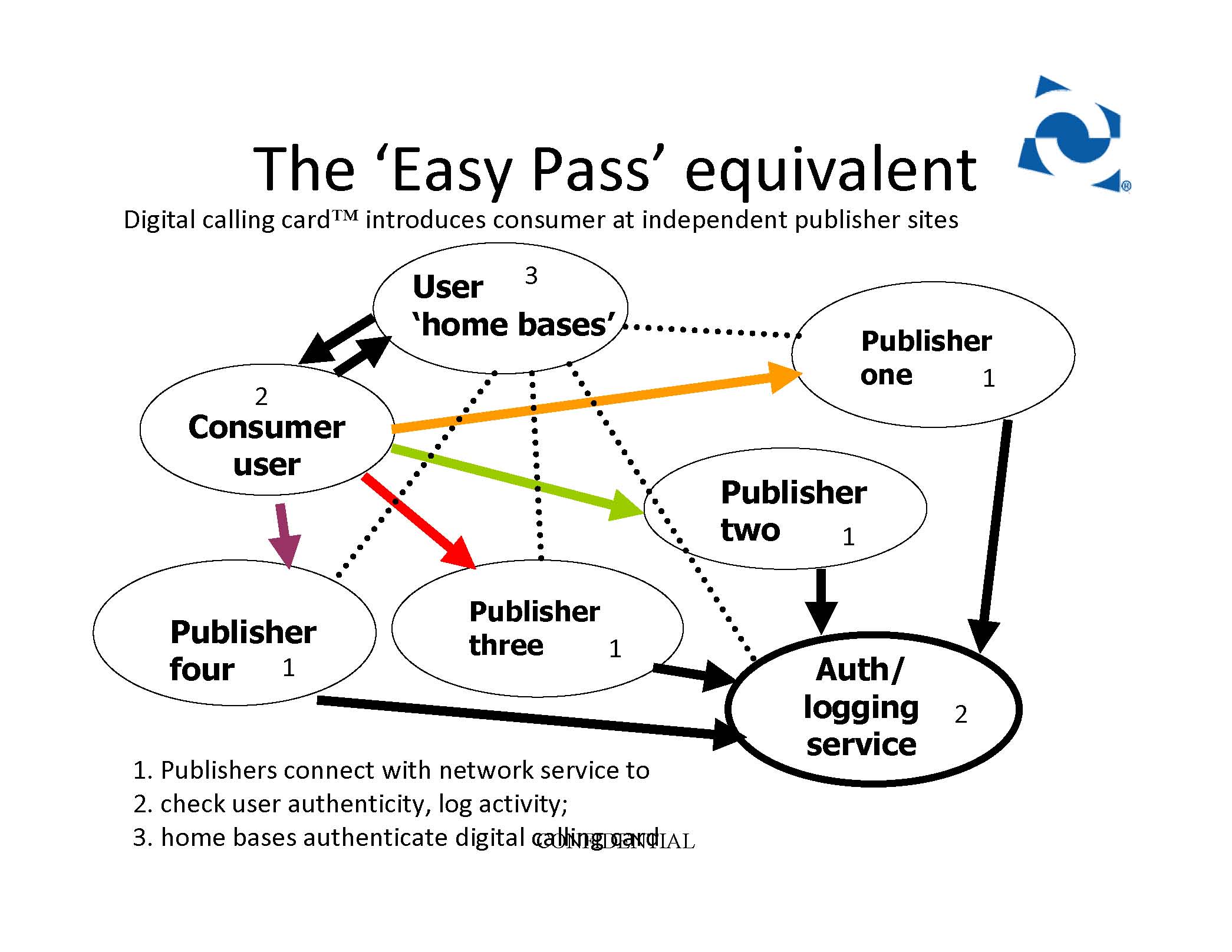

What publishers and content creators gain is the ability for any content item to easily reach any consumer, with content fees and/or advertising revenue flowing back to content owners/originators. This is possible by "sharing" users - via a "federated authentication" service.

In 1994, we figured the "home base" was where the consumer had their account, and where personal demographic and personal interests data were stored - to be shared only with the user's permission. Actually, newspapers were agents for the consumer in the old physical-delivery world. They licensed syndicated content and wire stories, added local news and commerce to create a useful information stew for communities. We thought they should be given the technology to continue in that role in cyberspace. But it didn't exist. Because the information would have to be personalized and procured and resold by the agent in a nanosecond. And there would have to be an accounting system to track and settle all of those atomic content transactions. Have you ever used a transponder on your car to pass through toll booths without stopping? You know how those "easy pass" systems now interoperate from state to state. Imagine the information ecosystem starting to look like this:

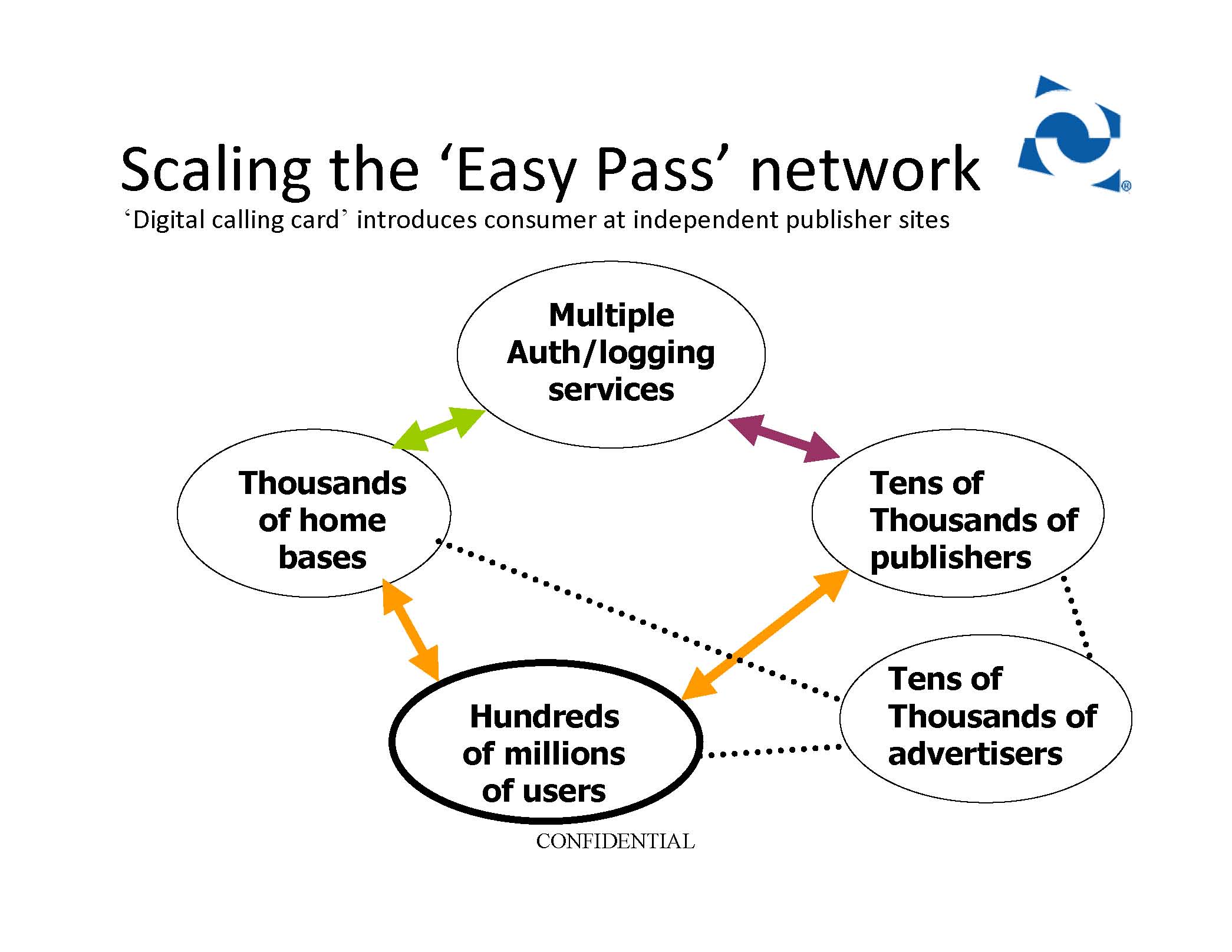

Now the Internet is a deep, wide place, and so its fairly likely that just one authentication and logging service (the transaction logger and trust/identity manager) isn't going to be enough. That would put one entity - or one nation - in a role akin to Big Brother. So we envisioned a network with authentication and logging services that would "talk to each other" and exchange data - although not personally identifiable information. And if you became distrustful of one network's authentication and logging service, you could quit it and sign up with a different network. So that ecosystem would look like this:

Perhaps Google would be one of the authentication and logging services. Facebook might run one. Microsoft another. Amazon another. The banking industry, with its good friend IBM, might run another. Perhaps governments would each run one. But the crucial challenge is to avoid going back to the "silo" days of AOL and Compuserve. To use another physical analogy - we want your web identity to be a "passport" that gets you in and out of silos/networks with little hassle. Virtual travel should be easy!

Virtual travel should be easy! No stopping at tollbooths and fumbling for money. No need to present your credentials at a checkpoint. All of that handled by your information valet, transparently governed by rules made by an international public-benefit organization.

That's why we need an Information Trust Exchange Governing Association - a public-benefit organization with global perspective and governance - that can make and enforce protocols and business roles for being a part of the network. Like Visa, it would register any consumer users itself. Think of it as designing the rules and playing field for football so that teams can then engage and the public can be entertained.

Or making a market for digital information.

For more about this idea, see: From Paper to Persona: Managing Information Overload and Sustaining Journalism in an Attention Age.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE

Federated Identity

Clickshare’s mission is to make the marketplace for digital information

Today, Clickshare offers publishers and other clients the most reliable system for mobile reader registration, authentication and online subscription management.

Ultimately, we are working toward our vision of a Federated Identity Management network that will offer content owners:

- Easy sign-up for a single account that can be used for content purchases at a growing list of Clickshare-enabled websites.

- Sharing of news and other content within a network of affiliated Clickshare-enabled websites, providing free or reduced rate access to registered customers, while charging for access to non-customers.

Under Clickshare’s patented “Four Party” approach to trust, identity and information commerce, we have no direct consumer relationships. When our publishing clients ask us to manage user registrations and payments, we do so only as their agent. The client (or their end user) owns all the information we capture, and Clickshare has the authority to use it only as needed to provide services to the client.

How Clickshare was set up to enable a shared-authentication user alliance

Clickshare gives a consumer access to lots of websites, without having to pass around personal information, or register repeatedly. The consumer can buy quickly, easily and securely with charges ending up on one account.

The system permits single registration, but also universal log-in, or sign-on, to multiple, independent websites which participate. It protects user privacy by avoiding the need for a massive central database.

The Clickshare backend basically does nothing except serve as a proxy for audience owners, forwarding and verifying the authentication of their own users, and logging the activity of those users at participating websites. The logs, however, contain only a one-time alpha-numeric which only the user's home base can map to an identified user. So Clickshare knows the user is unique, but doesn't know who the user is.

This elegant architecture is what makes Clickshare the ideal "federated authentication" service. Clickshare reliably shares among websites the fact that a user is "authentic", but doesn't, itself, need to know who that user is.

The Clickshare Service was conceived in 1994 and prototyped in 1995 and 1996. In news releases on PR Newswire back then, we described its unique features in these words:

- One-account, one-ID, single sign-on for users to multiple websites.

- No central data repository of private consumer data.

- Ability to log transaction details of purchases across all Clickshare-enabled websites.

In that era, we described Clickshare as a "micropayments" system, not recognizing that was a feature of the service but not the fundamental value proposition.

We conceived Clickshare originally as a solution to a problem which we foresaw newspaper publishers having -- how to hold onto users. We designed the system to allow a user's "home-base" newspaper -- that was the phrase we used -- to maintain and control the billing and customization relationship with the user. And yet the home base would have the ability to help that user find and pay for information from multiple other sources.

We called this, as early as 1995, "distributed-user management" (not a good marketing term, since it's acronym is DUM, but descriptive). Today we refer to it as "distributed customer management." (DCM sounds better).

The notion of keeping control of the user base out of the hands of a central "Big Brother" type authority was absolutely the bedrock of our idea and technology. It was natural for a publisher and journalist to be sensitive to this. In all the years since 1994, we have been continually amazed at the litany of dot-com's which tried to control the user and so ended up with no users because nobody would cooperate with them.

Amid all the wreckage of dot-gones, Clickshare stands and thrives because we started with a very simple premise -- create a marketplace for the exchange and sharing of digital content among distributed, independent audience owners.

SYMPTOMS OF CHILDHOOD:

The charge plate and the off-limits Xerox machine:

WHEN WILL THE INTERNET GROW UP?

WILLIAMSTOWN, MASS., Nov. 15, 2010 - Since the Internet burst from its academic and defense origins in the mid-1990s, people who own "content" have been troubled by two things: How to get paid, and how to keep from being ripped off.

Let me illustrate with two anecdotes from my childhood.

When I was a boy, my mom used to let me paw through her handbag. I used to be fascinating by the array of "charge plates" she kept for a dozen or more stores. These aluminum strips, smaller than today's plastic credit card, carried her name and address and the unique number that was her revolving charge account - a different number for each store. Each month she got 12 bills, or at least bills from each store she had patronized.

Today, my mother has two "credit cards" which serve the same purpose.

Anyone who wonders whether the Internet needs a shared-authentication infrastructure for single sign-on and digital transactions need only refer to the example of my mother's aluminum-plated handbag.

Momentum is building for a shared-user network for trust, identity and information commerce. that Clickshare. The U.S. newspaper industry should be thinking about a universal "travel pass." It's the only industry that has both content direct, account relationships with at least 45 million paying customers. We've written a brief summary of how Clickshare enables this sort of approach, going right back to Clickshare's conception in 1994. Watch for the formation of a news industry collaborative to get behind the "travel pass" concept.

At the heart of all of this effort is a desire to make it easy for consumers to transaction with multiple websites without having to pass around private information or create multiple accounts - a so-called "single sign-on." Although the idea was pioneered by Clickshare in 1994, others since have caught onto it. The newspaper industry has been considering shared user management for years, and even tried to pull it together in 1997 with the New Century Network.

DO YOU MAKE IT HARD OR MAKE IT EASY?

The second anecdote from my childhood involves the Worcester, Mass., public library. I remember going there in the early 1960s and finding signs on the Xerox-brand photocopier saying that it was illegal to copy books and periodicals on it. I remember, as a kid, finding that rather absurd. What else was going to be copied in a library? Are we going through the same learning process online right now? Did the copy machine finish books as a viable business? On the contrary, the copy machine has probably contributed more to the sale and dissemination - the marketing - of intellectual property than any other single invention.

When will we stop viewing perfect digital copies as a danger and instead view them as the greatest marketing opportunity to hit music, text and multimedia entertainment? The key is to make it easy for consumers to do the right thing - buy information at a reasonable price - rather than trying to make it hard to do the wrong thing - steal it.

And how do you make it easy?

In the entertainment, software and book businesses, much of the hand-wringing until a few years ago was not so much about how to get paid, but how to make sure you don't get ripped off. Companies like Sealed Media, Reciprocal, ContentGuard, RightsMarket, InterTrust, Preview Systems and Softlock Services all tried - and failed - to provide "locking" technologies which would somehow allow a consumer to get one-time or limited-time access to music, sofware or text objects, without being able to pass along the object.

But all of them failed. And into that void walked Apple and its iTunes Music Store - which made purchasing songs by the click completely simple. Eventually, the record labels even accepted Apple's decision to remove any digital-rights-management protection for the songs - because consumers were tired of having trouble moving their music from device to device.

One thoughtful approach a decade ago came came from Lawrence Lessig. He argued in his book, The Future of Ideas: The Fate of the Commons in a Connected World, (Random House) that it was time to develop a theory of copyright law based upon "compensation without control" - a system of almost open access to copyrighted materials where the owner must permit use for reasonable compensation.

Lessig's ideas were embodied in The Creative Commons. But what's now needed to make Lessig's idea work better for information commerce is agreement on a way to authenticate users as they access copyrighted material, and record their use. The marketplace can take care of the pricing function.

That's the ultimate vision Clickshare has held since 1994. Limit the gatekeeping role to nothing more than authentication and logging (recording clicks). Vendors own their content; retailers (or "Information Valets"), own their customers. All Clickshare - or an industry consortium Clickshare supports – need do is create the rules and infrastructure - the marketplace - for exchange to happen.

In the next few months, major companies will be making decisions about how to eliminate the metal charge plates -and how make it easy to buy instead of hard to steal. Clickshare can help.